Earlier this year, Dezeen teamed up with luxury kitchen appliances brand Scholtès to investigate a fascinating trend: the cross-pollination between the worlds of food and design. The main focus of our research was the Milan furniture fair in April, where we conducted video interviews with designers and chefs and filmed many of the food-related events taking place in the city. Jump to the report. Jump to the videos.

We then undertook an extensive survey of activity over the last couple of years and distilled it into this report, which we have called Food and Design. It aims to capture the whirlwind of activity in this dynamic area, and suggests where the love affair between design and food might take us.

The report (below) explores not only food itself but the way it is prepared and presented, and examines the changing role of the kitchen – the place where food has always been prepared and, increasingly, the room that is the heart of the home.

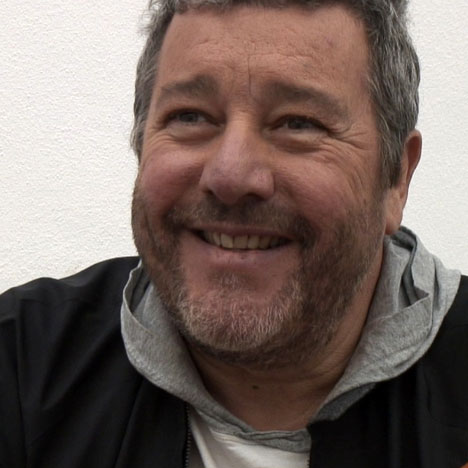

Marcus Fairs, editor-in-chief, Dezeen

About Scholtès

Scholtès is the luxury kitchen appliances brand which fuses professionalism and elegance. Scholtès launches into the UK from September 2010 with wider availability by April 2011, and is previewing its appliances Collection S3. S3 comprises an extensive full range of kitchen appliances, with pieces combining sophisticated functions with highly intuitive technologies.

Food and Design: a report

by Dezeen for Scholtès

.

.

Contents

Part 1: food and design at the same table

Food as material

Designing the experience, not the food

The past is the future

Provenance

Water

Part 2: the changing kitchen

The kitchen merges with the dining room and lounge

The workshop kitchen

Fast kitchen, slow kitchen

The communal kitchen

More authenticity, less gadgetry

The high-tech kitchen

The professional kitchen

The growing kitchen

The ethical kitchen

The ancient kitchen

The Stone Age kitchen

The ritual kitchen

The sharing kitchen

Kitchen as theatre

Epilogue: the future of food

Part 1: design and food

at the same table

.

The worlds of design and food are coming together. Leading contemporary designers are turning their attention to all aspects of food culture: the ingredients and their preparation, the culinary process, the design of the kitchen and the objects within it, and the serving and enjoyment of food.

Likewise cutting-edge chefs, kitchen brands, restaurateurs and supermarkets are increasingly turning to designers to give their offerings added cultural relevance and commercial appeal.

In design circles, food has emerged as one of, if not the, most exciting areas of exploration. At the Milan furniture fair in April this year, a substantial proportion of the exhibitions involved food in one way or another. Everywhere you looked, designers were turning galleries into live cooking events (such as Public Pie, above), running food workshops, presenting their visions for the perfect dinner or even growing vegetables.

Also in Milan this year was Eurocucina (above), the giant biannual kitchen design show. To celebrate, Cosmit, the company that runs Eurocucina and Milan’s official Salone Internazionale del Mobile (International Furniture Fair), this year laid on a spectacular exhibition called Tutti a Tavola! (Everyone to the table!), which explored the relationship over the centuries between food and high culture in Italy. Never has the design world been as infatuated with food as it was this year.

The two most important design schools in the world, the Royal College of Art in London and Design Academy Eindhoven (above) in the Netherlands, both presented food-related work in their Milan presentations. Anne Mieke Eggenkamp, chair of Design Academy Eindhoven, said food is one of the two hottest topics on the contemporary design agenda:

“Food is a very hot topic. I think food and textiles are the two topics that will be key in the next ten years.” See the video interview with Anne Mieke Eggenkamp.

There is also a new wave of designers and organisations that specialise in preparing food or organising food-related happenings and events: Italian group Arabeschi di Latte, Dutch designer Marije Vogelzang and Eat Drink Design (above), a Dutch group that combine design exhibitions and dining experiences, are just three outfits who are building careers out of this new and exciting field.

Vogelzang for example, a young Dutch designer already famed for her food happenings, has just opened Proef (above), an “eating design” restaurant, in Amsterdam, that presents a holistic design experience and serves organic, seasonal, locally sourced produce.

As designers integrate food into their work, chefs are reciprocating by introducing design to their cuisine. French chef Marc Brétillot specializes in “culinaire design” (above) while Finnish chef Antto Melasniemi recently presented Hel Yes! (below), a pop-up restaurant where regional dishes were presented in a fairytale environment furnished by Finnish designers and artists.

The cross-fertilisation between food and design is already having a marked impact on the way people prepare and enjoy food, as new ideas get absorbed by the restaurant trade and the supermarkets. That change looks set to accelerate in the near future as the ideas been generated today enter the mainstream.

Food as material

The most obvious manifestation of designers’ new fascination with food is the way they now view foodstuffs as a material to work with. Like wood, metals and plastics, food is something they can take into the workshop, and experiment with.

“I’m a product designer and I like also to work with food. I see it as a material. It brings more emotion from the people”

- Marieke van der Bruggen, designer, Public Pie. See the movie about Public Pie

“We are trying to design food as we design [other] materials”

- Olivia Decaris, graduate, Royal College of Art

Above: Pouch, a malleable carafe for wine and other drinks, by Olivia Decaris.

The end result is not always something that can be eaten. Examples range from the jokey – for example the Bread Shoes by R&E Praspaliauskas, which are, quite literally, shoes made of bread; or the semi-serious experiments on view in Milan this year that involved exploring the structural properties of materials made from rice and potatoes by making chairs out of them – to serious scientific research into how advanced manufacturing techniques such as rapid prototyping could be used to make new edible forms.

Above: Bread Shoes by R&E Praspaliauskas

More often though, avant-garde designers are interested in the symbolic and aesthetic qualities of comestibles, and in investigating new ways of making things that are inspired by culinary processes. For example, Italian designers Formafantasma recently created a beautiful series of vases, bottles and bowls made of baked flour, coffee, spinach and other foodstuffs.

Above: Baked by Formafantasia

In fact, while they are fascinated with the potential of food as a material, contemporary designers are somewhat reluctant to “design” food itself, feeling that the notion of “designer food” is somewhat repellent and goes against the current preference for a more naturalistic, assemblage-based approach to food preparation and presentation.

“Personally I’m not really fond of really designed food like they do nowadays in the high cuisine restaurants like one stripe of vinegar and a few leaves almost like a piece of art. I like more the rustic part of the whole food experience”

- Kiki van Eijk, designer. See the video interview with Kiki van Eijk.Below: Table-Palette by Kiki van Eijk

This chimes with the feeling that molecular gastronomy – with its emphasis on transforming ingredients via scientific processes – is going out of fashion in elite restaurant circles.

“Perhaps molecular is nearly finished [and] everybody can evaluate another way. And the better way better perhaps is more natural, more radical”

- Alexandre Gauthier, Michelin-starred chef (above). See the video interview with Alexandre Gauthier

Above: dish by Alexandre Gauthier. Below: dish by René Redzepi of Noma.

In its place comes a focus on more hand-crafted food, served in an informal way, and often featuring local produce and methods. At this year’s World’s 50 Best Restaurants awards, the Best Restaurant in the World accolade went, for the first time in several years, not to the molecular gastronomy of Ferran Adrià’s El Bulli or Heston Blumenthal’s The Fat Duck, but to Noma (bel0w), a Nordic revival restaurant in Copenhagen run by René Redzepi, that serves dishes involving seaweed and curds from Iceland and musk ox from Greenland.

Designing the experience, not the food

In terms of restaurant design, the most influential interior of recent years is Matsalen and Matbaren, a dining room and food bar in Stockholm, run by Swedish revivalist chef Mathias Dahlgren and designed by Ilse Crawford.

Above and below: Matbaren at Grand Hotel Stockholm, designed by Ilse Crawford

Dahlgren serves contemporary, hand-crafted takes on traditional Swedish dishes while the two spaces – one serving sit-down meals and the other serving quicker bar snacks, are fitted out in an eclectic, informal manner, with vintage Scandinavian furniture mixed with contemporary pieces and folkloric touches.

The design (above and below), which has won as many awards as the food, is intended to compliment the food “physically and emotionally, sensorialy and subliminally”. This focus on craftsmanship, local culture, informality and sensuality sums up the direction cutting-edge food is going right now.

While advanced science may shape the food of the future, today’s designers are more interested in keeping food as unprocessed as possible. Philippe Starck points out that there are essentially just two trends when it comes to food: the artificial, processed “fast” foods and ingredients that still dominate supermarket shelves; and the return to organic, unadulterated “slow” food. Designers are mainly interested in the latter.

“For the organic food, the less it’s designed, the better it is”

- Philippe Starck, designer (below). See the video interview with Philippe Starck

Rather than mess with the ingredients themselves, designers are instead examining the way food is prepared and the implements involved; and the way it is presented and enjoyed. They are also fascinated by the kitchen and devote much energy to exploring new kitchen concepts. Examples of all these can be found throughout the rest of this report.

The past is the future

Far from gazing into the future, as you might expect, contemporary designers seem to be more interested in learning from the past, or from other less developed cultures, and re-evaluating lost knowledge about food. This chimes with wider trends that have swept through the design world in the last few years, noticeable for example in the return of craft, decoration, vernacular forms and traditional materials in avant-garde design.

This is evident in projects such as Global Street Food, an exhibition curated by Mike Meiré for kitchen brand Dornbracht in 2009 and which consisted of vernacular food stalls from around the world gathered together in a gallery as a kind of junk art installation. Exhibits included a grill mounted on a bicycle wheel from Zaire and a cheese stand improvised from a shopping trolley. For Dornbracht, the exhibition offered the opportunity to learn lessons from street vendors that might be applicable to their kitchen designs.

Above: grill from Zaire, part of the Global Street Food exhibition curated by Mike Meiré for Dornbracht

Similarly, architect David Chipperfield’s recent, acclaimed tableware collection for Alessi, called Tonale, is based on ancient Korean stoneware (and features colours inspired by Italian still-life painter Giorgio Morandi).

Above: Tonale by David Chipperfield for Alessi

Provenance

In our globalised age, a new set of values is emerging that prizes the local and the hand-crafted over the homogenous and the manufactured. The worlds of food and design are both independently being massively influenced by rising demands for more ethically sourced products that are both environmentally and socially sustainable.

The notion of provenance – where something comes from – has become highly important in this new value system, with people expecting transparency and honesty about the origin of goods and ingredients.

Fairtrade, where workers in the developing world are paid a fair price for the commodities they grow, and the Locavores movement, where people only eat foods grown within a certain radius of where they live, are two examples of this.

Another example of the rising importance of provenance comes from last year’s Milan furniture fair, where a group of designer from Eindhoven put on a show where everything was both designed and made in the Dutch town. The Jewels and Joules exhibition even featured a kitchen serving canapés made from ingredients grown in the town.

Water

Water is perhaps the ingredient, or material, that is attracting most attention from designers. The life-giving liquid has taken on renewed symbolic importance given the pressures of global warming, pollution, and tensions between nations over scarce water sources, but also because the simple act of sharing a carafe of water is one of the most basic, but humane, activities.

There have been numerous design projects about water recently, for example Top Tap, a design by Neil Barron that won a competition for a new jug to encourage people to drink tap water, instead of bottled water, in London restaurants. The glass carafe features a spout shaped like a tap.

Above: Tap Top by Neil Barron

At the Design Academy Eindhoven show in Milan this year, Lizanne Dirkx presented a ceramic water fountain designed to encourage the same social activity in offices as is generated by water coolers, but which instead dispenses tap water. The piece uses the natural cooling properties of ceramic.

“In Europe you can drink water from the tap but it’s not a social activity to do it, especially in offices. So she created a kind of sustainable, beautiful ceramic piece, where with other people you can share and drink water.”

- Anne Mieke Eggenkamp, chair, Design Academy Eindhoven. See the video interview with Anne Mieke Eggenkamp

Above: Drinking Fountain by Lizanne Dirkx

Part 2: the changing kitchen

.

The domestic kitchen is the place where most people have most of their experiences with food and unsurprisingly it is the subject of the most intense investigation by designers. Changing lifestyles and attitudes are also helping to drive profound change in what was once the most utilitarian of rooms.

The kitchen merges with the dining room and lounge

The kitchen is moving from the back of the house to its centre. No longer merely “a room used for cooking and food preparation”(Wikipedia’s definition), the kitchen is becoming the central space for both living and entertaining in the home, and the space around which home life revolves.

The kitchen is merging with other rooms in the house – notably the dining room and the lounge – to become the main social hub for living and entertaining. Whereas in the past each room had its peculiar set of furnishings and gadgets – worktops and cookers in the kitchen, table and chairs in the dining room, sofa and TV in the lounge – the new “super-kitchen” combines all these.

“The dining room comes into the kitchen, the kitchen becomes a dining room. We can stay a long time in the kitchen. That means the living room disappears, so there is only one room, which is the kitchen.”

- Philippe Starck, designer

At the giant Eurocucina kitchen show in Milan this April, leading brands were showcasing kitchens featuring widescreen TVs, armchairs, bookshelves and cabinets containing objects d’art and photos instead of just cooking utensils. Many featured built-in computers and iPods; others had indoor gardens or aquariums.

Alno was one of many brands showing hybrid kitchen/lounges, with a comfy sofa, a rug and a wall-mounted TV surrounded by more traditional kitchen storage units.

Above: Alno’s stand at Eurocucina

In an exhibition organised by Wallpaper* magazine in the centre of Milan this year, Young German designer Gitta Gschwendtner presented a radical prototype kitchen that took the idea of the kitchen merging with other rooms even further. Her Drawer Kitchen is a kitchen island crossed with a giant, deconstructed chest of drawers, capable of storing not just food and kitchenware but also books, toys, CDs and even clothes.

“The Drawer Kitchen is designed to be positioned in an open plan kitchen/dining area with the drawer front facing the dining area and the sink back facing the rest of the main kitchen. It creates a link between food preparation and the social aspect of eating.”

- Gitta Gschwendtner, designer

Above: Drawer Kitchen by Gitta Gschwendtner. See the video interview with Gitta Gschwendtner

Kitchens are correspondingly getting bigger to accommodate all these mixed uses.

“Today when people are looking at a kitchen project they are looking at removing the walls, removing the doors and creating much more open living spaces that incorporate not only the kitchen and appliances but also the eating area and indeed some parts of the lounge. So the whole area becomes the social centre of the house. People are making quite radical changes to the structure of the property in order to make that change.”

- Nigel Taylor, brand director, Scholtès UK

The changing function of the kitchen is driven by a number of factors. Firstly, the traditional spatial separation between cooking and eating has dissolved. Once, the kitchen was located in the remotest part of the house and was dedicated only to food preparation; meals were then transported to the dining room – another single-function room that was rarely used outside meal times – where the family congregated to eat. The food preparation process was hidden from diners and so was the clearing up; dirty plates were quickly whisked back to the kitchen.

“The way we take food has changed, that has changed architecture, and that has changed design. Before, when my parents, the dinner, the lunch was around a table. It was in the dining room, it was a closed room, and the kitchen was very far, because the architecture came from the castle and in the castle the cooking was made by slaves very far away, either outside the castle or in the basement.”

- Philippe Starck, designer. See the video interview with Philippe Starck

Today, by contrast, cooking has become a sociable leisure activity, in which hosts prepare food in front of their friends, with guests helping out. Cooking is seen as a relaxing or even therapeutic activity, rather than a chore.

“Nowadays kitchens are quite open plan and people like to talk while someone else is cooking a preparing.”

- Gitta Gschwendtner, designer

The workshop kitchen

For men, the kitchen seems to have taken over from the garden shed as a place to experiment and tinker. The concept of the “workshop kitchen” – a slightly cluttered but functional and authentic working environment – is taking over from the status-symbol aesthetic of the minimalist look. The focus is no longer on monolithic forms and vast expanses of plain surfacing materials but is instead on the food itself, and its preparation.

Kitchens with a mixture of different materials and finishes are becoming more common. Instead of being hidden away in drawers or cupboards, cooking implements and tableware are increasingly kept in open-fronted storage units, on shelves or on work surfaces, increasing the feeling of the kitchen as a workshop.

Bulthaup was one of the first big kitchen brands to explore the workshop kitchen when they launched their B2 kitchen in 2008 (top and above). This is based on a workshop layout and is made up of three main elements: a “workbench” housing the sink and cooker, “tool cabinet” for utensils, crockery and food, and appliance cabinet for the oven, dishwasher and fridge.

Above: B2 by Bulthaup

Also in 2008, Schiffini exhibited the Mesa kitchen by Argentinian designer Alfredo Häberli; part workshop and part living room, the open-plan space is based on Häberli’s memories of large family kitchens in his homeland – large, informal, communal spaces for preparing and enjoying food.

The kitchen features elements that appear to have accumulated over time rather than being integrated; Häberli describes the approach as being “governed by a pleasant untidiness and not the aseptic architectural space which we see so often nowadays.”

Above: Mesa kitchen by Alfredo Häberli for Schiffini

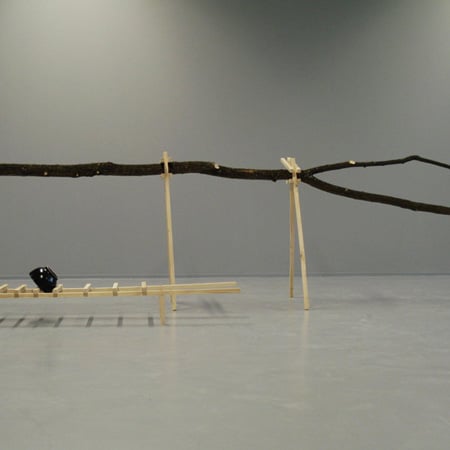

Young French designers Matière A have reacted even more strongly against the hegemony of the monolithic kitchen, creating in 2009 a storage, draining and worktop system called Vaisselier Système D out of rough tree branches that resembles a camp canteen more than a domestic kitchen.

Above: Vaisselier Système D by Matière A

Fast kitchen, slow kitchen

Domestic kitchens are subject to contradictory forces as adults are increasingly interested in the notion of “slow food” and more leisurely, informal dining, while the hectic, mobile lifestyles of teenagers and young adults means their meals are often taken on the fly and are disrupted by mobile phone conversations, friends arriving and departing and so on. So the family kitchen has to be able to cater for both the lingering lunch and the snack-on-the-run.

At the same time, the kitchen is becoming the stage for more and more non food-related activity, hence the introduction of sofas, armchairs, widescreen TVs, rugs and other items traditionally seen in the lounge.

One manifestation of less structured dining patterns, according to Philippe Starck, is a tendency towards higher table heights, with the standard 72cm table increasingly being replaced in favour of the 1.4m table. This bar – or worktop – height table is more suited to informal dining and the comings and goings of different people.

“They [the younger generation] want movement. That’s why this 72cm table more and more disappears, goes to 1.4 metres, meaning it’s bar height, which is very interesting because it means you’re the same level as your son or daughter when they ask you for the key of the car to go to a party. That means this height is more dynamic. It’s a big change, structural change, in the way you eat longer or faster and how that changes design.”

- Philippe Starck, designer

Starck goes further, imagining a time in future when increasingly mobile lifestyles herald the end of the dining experience altogether:

“The next generation will have no more furniture for eating because they will not need it. The food will always be during movement, during action, during the day and night. The idea to stop and sit around a table is obsolete for the next generation.”

Starck has put this thinking into practice at two recent hotels – the SLS Hotel in Beverly Hills and the Palazzina Grassi in Venice, both of which feature dining rooms with bar-height tables, the latter having a 7m communal table as its centerpiece.

Above: SLS Hotel at Beverly Hills by Philippe Starck

Above: Palazzina Grassi by Philippe Starck

The communal kitchen

The long, communal table has returned to favour, and is now used not only for dining but for other activities such as work and homework, reading, watching TV as well as food preparation. In 2008, radical Dutch architects UNStudio pushed the concept to the extreme when they presented The World’s Longest Table For All Cultures at the imm cologne furniture show in Cologne, Germany. This 55m-long multifunctional table was designed to highlight the way the kitchen has today become a place for a wide variety of activities:

“The present-day kitchen is seen as a place of numerous activities, which go beyond the traditional of a kitchen as a purely place for the preparation of food.

The kitchen is perceived as a stage for cooking as a performance, a space where food can be raised to an art form, where experiments and innovation take place. The ways in which food is prepared and consumed show the effects of globalization: the contemporary kitchen is truly a place where cultures meet.

But even more the kitchen is a space for different types of social gatherings. The kitchen is the scene of family get-togethers, friends socializing, work-related activities, day-to-day dining, formal entertaining, late-night snacks, Sunday brunches, hurried breakfasts and so on.”

– UNStudio, architects

Above: The World’s Longest Table for All Cultures by UNStudio

More authenticity, less gadgetry

With the kitchen becoming a more homely and pragmatic space, the obsession with ostentatious gadgets seems to be waning. People are increasingly seeking natural food made from the freshest, purest ingredients and accordingly they are less inclined to submit their food to artificial processes. Food preparation has become more tactile; hand-held implements such as paring knives, pestle and mortar, lemon reamers, apple corers and potato mashers are preferred to food processers, juicers, bread makers and blenders.

I never have time for gadgets, never have time for the artificial, never have time for the superficial.”

- Alexandre Gauthier, Michelin-starred chef. See the video interview with Alexandre Gauthier

The return to basics has even seen a rediscovery of ancient kitchen implements – see The Stone Age Kitchen, below.

The high-tech kitchen

Despite the trend away from gadgetry for food preparation, kitchens are increasingly equipped with digital media devices such as widescreen TVs, hi-fi systems, computers, iPods and iPads, which can be used to access recipes from the internet as well as for playing music and watching movies. This can be seen as part of the more general merging of the kitchen with the lounge.

Singaporean manufacturer Bi&L has taken the concept of the high-tech kitchen furthest, presenting at Eurocucina this year a “lifestyle” kitchen with a flat screen TV that descends from behind storage units at the touch of a button, servo-controlled pop-up power points that sit flush with work surfaces until they are needed and even a motorised table that can rise and fall between dining height and bar height on demand. See the video about the Bi&L high-tech kitchen.

Technological advances in other sectors could potentially revolutionise cooking in the future. For example, developments in 3D manufacturing that allow three-dimensional objects to be “printed” at low cost mean such techniques could soon be used in the domestic kitchen. Electronics brands including Philips are already experimenting with devices that may one day offer domestic cooks the ability to conjure miraculous creations akin to those produced by proponents of “molecular gastronomy” such as Heston Blumenthal.

The professional kitchen

However, discretion is most often the keyword when it comes to the introduction of sophisticated technology in the contemporary luxury kitchen. Consumers are demanding professional-grade equipment and a no-nonsense “professional” aesthetic – simple, robust-looking appliances fabricated in quality, long-lasting materials.

Above and below: kitchen by Scholtès

“Consumers today are really looking for professional levels of performance in their appliances. They watch chefs on television, they go to Michelin starred restaurants, they see really wonderful food and they want to replicate that in the home and they know that to be able to do that, as well as absolutely superby ingredients, they need great appliances on which to cook their food.”

– Nigel Taylor, brand director, Scholtès UK. See our video interview with Nigel Taylor

Above: Scholtès 110cm range cooker. Below: Scholtès professional hob

Appliances may contain advanced technology or be manufactured using sophisticated processes, but this sophistication is subtly expressed or even hidden. This fits with wider trends towards more restrained expressions of luxury and wealth born of today’s straitened economic times, and a general trend towards simpler, healthier lifestyles.

With the emphasis increasingly on using the freshest, most wholesome ingredients, cooking appliances are accordingly expected to retain flavour and goodness, leading to greater demand for gentler processes such as steaming, slow cooking and induction methods.

“In terms of healthier eating we have seen different sorts of technology coming into the kitchen. People are becoming familiar with steam cooking for example, which is a cooking method that allows the goodness to be retained in the food, they’re more interested in slow cooking, where flavours can be really retained by reducing the ferocity of the cooking process.”

- Nigel Taylor, brand director, Scholtès UK

Top: Scholtès Multiplo cooker. Above: Scholtès 45cm collection

The growing kitchen

While the “engine” of the contemporary luxury kitchen is the ultra-high quality, professional-grade appliances, the overall look of the kitchen is becoming more rustic and sentimental.

The traditional farm kitchen or country house kitchen – where many of the ingredients are grown in nearby fields or in a kitchen garden outside the back door – seems to be the romantic progenitor for many contemporary kitchens. It is increasingly common for kitchens to feature plants (both decorative and edible) and animals (both pets and food sources).

With people increasingly concerned about the provenance of their food (see above), there is logical movement towards growing it yourself. In recent years there has been a surge of interest in local sourcing of food and in urban farming – whereby food is grown closer to population centres, thereby reducing the time and energy required to transport it and making it easier to be sure that the food has been produced to high standards.

More recently, avant-garde designers have begun exploring how the kitchen itself could become a source of fresh food. Examples include The Farm Project, a concept by art director Mike Meiré for kitchen manufacturer Dornbracht, which featured livestock pens, fish tanks and herb gardens inside a functioning kitchen and French designer Mathieu Lehanneur’s Local River, a domestic tank for breeding fish for consumption that doubles as a vegetable garden; salads and greens are grown in glass pods floating on the water and are fertilised by fish waste.

Above: The Farm Project curated by Mike Meiré

Above: Local River by Mathieu Lehanneur

The psychological and physical benefits of living in proximity to plants and animals are well discussed; French botanist Patrick Blanc has become famous for his “vertical gardens” – plant-clad walls that can be used indoors as well as out; while Lehanneur has designed Bel-Air, an air purifying system that uses plants instead of mechanical or chemical systems to remove pollutants from the air. Concepts such as these seem set to become increasingly popular in kitchens, which are after all the source of most household odours.

The ethical kitchen

Ethical considerations have risen to the fore when it comes to choosing a new kitchen. People are increasingly asking questions about the provenance – where and how it was grown – of the food they prepare and insisting that their kitchens are as sustainable as possible, consuming the least possible amounts of energy and water and creating the smallest amount of pollution and waste. The kitchen is after all the most energy-intensive room in the house, and the one that generates the most waste.

“We find people investing in luxury kitchens are not particularly challenged by the cost of the electricity bill. But they have a very strong social conscience. And when they’re investing in appliances they want to be sure they’re going to use the minimum of energy, the minimum of water, and have the absolute minimum impact on the environment. Young people and children really like to get involved in the appliances; they’re not so worried about what can be cooked on them but they want to know that they use the minimum amount of energy and water. And they’re influencing some of the decision making of the parents in choosing a luxury kitchen.”

- Nigel Taylor, brand director, Scholtès UK

Avant-garde designers have begun to explore the notion of the “ethical kitchen” in recent years. In 2007, design student Alexandra Sten Jørgensen exhibited a concept kitchen made of recycled materials in which waste water was used to irrigate creepers growing up and over the worktops.

Above: Ethical Kitchen by Alexandra Sten Jørgensen

Earlier this year, designers Victor Massip and Laurent Lebot of Faltazi went a stage further, designing a conceptual system to reduce all forms of waste. Three “micro-plants” built into their Ekokook kitchen are used to store sorted solid waste to reduce the number of collections by local authorities; to filter and store greywater for re-use for watering plants; and to break down organic waste in an earthworm composter.

Above and below: Ekokook by Faltazi

Kitchen accessories and tableware are another area where the search for ethical solutions is having an impact. Mater, a new homewares brand, produces goods that are sourced according to strict humanitarian and ecological guidelines to ensure no harm is done either to the workforce (many products are manufactured in the developing world) or the environment.

Sustainable natural materials such as bamboo are increasingly used for kitchen implements; in 2003 leading designer Tom Dixon created a range of cups, bowls and plates called Eco Ware, made of 85% bamboo fibre mixed with water-soluble polymer. Resembling Bakelite, these objects gradually wear out with use but are completely compostable.

Above: From Fable to Table by Amelie Onzon

More radical still is an ethics-based project by Design Academy Eindhoven student Amelie Onzon. Responding to people’s mixed feelings about eating fois gras, Onzon designed a series of implements for farming geese which allowed the consumer to decide whether to improve the quality of the fois gras (and thereby lower the quality of life for the goose) or vice versa.

“We like fois gras, we think it has a fantastic taste, but we know somewhere in our mind and in our heart its not good to eat it because if you realise how it is produced. But you can decide where to buy, what you buy, what you order in the restaurant. With these pieces you can say hey, it’s up to me what I eat.”

- Anne Mieke Eggenkamp, chair, Design Academy Eindhoven

The ancient kitchen

Hand in hand with consumer demands for greener kitchens and more ethically sourced food comes a revival of ancient techniques for storing and preparing ingredients. In Milan this year, Design Academy Eindhoven student Jihyun Ryou presented a kitchen based on the memories of her Japanese grandparents, who used to store vegetables in containers or damp sand to keep them fresh without refrigeration. Besides being an energy-free storage method, she claims this technique also allows vegetables to retain their flavour better and for longer than under the often brutal conditions of the refrigerator.

“By storing your vegetables in sand with a little water, it’s better for the taste, no energy and you can keep the vegetables much longer than keeping them in a fridge which of course costs a lot of energy and the food is too cold so it doesn’t taste good.”

- Anne Mieke Eggenkamp, chair, Design Academy Eindhoven. See this project in our video interview with Anne Mieke Eggenkamp

Above: Shaping Oral Knowledge by Jihyun Ryou

In a slightly more extreme vein, London designers Postler Ferguson’s Nouveau Neolithic kitchen from 2007 pre-empts the credit crunch by presenting a primitive outdoor system for preparing meals from basic staples and foraged food.

Above: Nouveau Neolithic by Postler Ferguson

Before refrigeration, many cultures developed ways of keeping water and food fresh and cool, often by storing it in clay vessels which, as water evaporates through the porous clay, benefit from a natural chilling effect.

Several designers have recently adopted this technique to create contemporary cooling devices. For example, Anglo-Indian designers Doshi Levien’s Matlo water cooler is based on indigenous Indian coolers.

Above: Matlo by Doshi Levien

The Flow2 kitchen concept by Oregon designers John Arndt and Wonhee Jeong of Studio Gorm features double-walled terracotta containers for food storage instead of a fridge (and also features an earthworm composter like the Ekokook kitchen (above).

Above: Flow2 kitchen by Studio Gorm

The Stone Age kitchen

The interest in ancient techniques extends to the tools used in the kitchen. We have already discussed the trend away from gadgets towards more tactile, craft-based methods of preparing foods and there is a parallel move towards the use of primitive implements, which is part of a wider tendency among avant-garde designers towards more basic, raw forms. For example, New York designer Matthias Kaeding has produced NeoLithic, a range of ceramic kitchen knives that resemble Stone Age tools; while Swiss designer Christine Birkhoven created a series of rudimentary kitchen implements called Stone Tools which, as the name implies, are made of solid rock.

Above: NeoLithic by Matthias Kaeding

Above: Stone Tools by Christine Birkhoven

The ritual kitchen

The form and appearance of the kitchen is changing fast as we have seen, but the way the kitchen is experienced is perhaps changing faster still. Recent years have seen a rediscovery of the pleasures of cooking, dining and food-related socializing and people are increasingly focusing on heightening the experience of all aspects of food.

This could perhaps be due to the way that internet shopping and takeaway culture have reduced much of our experience of food to a phone call or a transaction, leaving us missing the tactile contact with raw ingredients.

Farmers’ markets, where people can buy produce from the people who grew them, are one manifestation of this, with the gourmet Borough Market in London being an upmarket example of the trend.

In Turin, Italy, a new supermarket concept called Eataly features an area where people can learn about food, watch demonstrations, take courses and learn how food products are made.

Designers too are increasingly interested in reintroducing lost rituals and experiences. At Design Academy Eindhoven for example, students – who come from all over the world – are actively encouraged to consider the cultural rituals associated with food:

“In Holland maybe students [are used to] eating in front of the television and just putting the food in your mouth and it’s done after five minutes. But the quality of being together with your friends, sharing those moments, taking care of how it looks, how it tastes, how the table looks – it does matter.”

“What we do with first year students is let them eat together. It opens up people’s minds. So students come up with new events. They design the moments of sharing food themselves, which is inspiring for not only us but also the fellow students… it’s a multicultural way of sharing, collaborating, feeling”

- Anne Mieke Eggenkamp, chair, Design Academy Eindhoven

There are all kinds of cultural rituals attached to dining and avant-garde designers are exploring these in their work, often digging deep into the past to find long-forgotten traditions.

Greek graduate Ioli Kalliopi Sifakaki presented a ritualistic interpretation of dining at the Royal College of Art show, held in the Ventura Lambrate district in Milan. Called Tantalus Dinner, her project features a ceramic dinner service cast from her own body parts; she then invited a dozen of her male friends to a feast served from the tableware. This ritual, and somewhat cannibalistic, dinner was based on a Greek myth in which a man called Tantalus boils his son Pelops and offers him up as food to the gods to appease them.

“The ritual of eating is the key element in my work”

- Ioli Kalliopi Sifakaki

Above: Tantalus Dinner by Ioli Kalliopi Sifakaki

The sharing kitchen

The fact that food brings people together has been seized upon by designers, who are keen to take their discipline away from the materialistic, status-driven obsessions of the recent past. Sharing food is a democratic statement in which communal pleasure is more important than any individual contribution and dining has become an ideal vehicle for expressing design’s new humanistic attitude.

“I very much think that cooking and dining are almost becoming part of the same thing. It’s much more informal, than, perhaps, in the past”

- Gitta Gschwendtner (above). See our video interview with Gitta Gschwendtner

Creating dining scenarios is today a common theme among young designers. Again at Ventura Lambrate, an exhibition called Total Table Design featured scenographies by a number of designers including Kiki van Eijk, who dressed a large table with objects of her own design based around a large terrine from which communal soup or stew could be served.

“Personally I think a good meal is an evening with friends around a table and a lot of courses, a lot of pure food, and the most important thing is that somebody made it for you. It doesn’t matter if its high cuisine or not. At my table the terrine is the basic thing of the whole set-up because that really symbolises the sharing altogether. You make one big pot with either a stew or a salad or a soup and you share it with everyone around the table”

- Kiki van Eijk, designer (above). See our video interview with Kiki van Eijk

Above: Table-Palette by Kiki van Eijk

Kitchen as theatre

The kitchen can increasingly be seen as a theatre in which the acts of preparing, cooking and sharing food become private performances for family and invited guests. The phenomenon of TV chefs has raised interest in the colour and drama of food preparation, and cooking is becoming an increasingly social activity, with friends and family helping out in what is becoming valued as a shared tactile experience, rather than the passive consumption of food and drink.

Not too long ago cooking meant standing alone at a stove facing the wall but in recent years the act of cooking has started to turn through 180 degrees, thanks to the rise of the “island” kitchen and kitchen layouts where the hob faces towards the dining area.

This trend has not escaped the attention of the world’s leading restaurants. The organizers of The World’s Best 50 Restaurants, announced just after the Milan furniture fair, declared:

“At the new number one restaurant in the world [Noma in Denmark] the chefs themselves come out and present the food at your table … Internationally there is a very strong trend for ‘raw cooking’ with a very relaxed style of dining … There is marked change taking place, which means that restaurants with starched table cloths and waiters in penguin suits are no longer considered the best”

- London Evening Standard, 27/04/10

At the Milan furniture fair this year, there were many young designers and avant-garde organisations exploring the boundaries of food as performance. The most entertaining was Public Pie, a cross between street theatre and a mobile kitchen and dining room in which Dutch designers Marieke van der Bruggen and Maaike Bertens prepared dishes for the public, who waited for cheese and tomato tart and apple pie while sitting on a bench warmed by the oven located beneath.

Above: Public Pie by Marieke van der Bruggen and Maaike Bertens

Public Pie, presented at the Ventura Lambrate district in Milan, is informed by the slow food movement and the contemporary interest in the provenance of ingredients (which are all prepared in front of your eyes):

“It’s about the total experience. It’s not just to give you a pie. It’s a little bit about slow living, you can see directly how pure it is and you can see every step with the apple, the peeler, the dough. And the end result. So it’s a very honest thing.”

- Marieke van der Bruggen (below), designer, Public Pie. See our video about Public Pie

At a gallery in central Milan, cult magazine Apartamento presented FoodMarketo, another presentation featuring live cooking as well as an exhibition of food-related designs. The organisers asked around 30 designers and cooks to design objects and present workshops in bread-making, sushi preparation, jam-making and so on, with the public invited to join in.

Above: FoodMarketo in Milan, April 2010

“I think we are trying to explain that things can be simple, and that the table is a good place to meet and to just be around and to share. Everybody is on the same level and we are just making food together and there nobody is more important than anyone else”

- Alex Bettler (below), Apartamento magazine. See our video interview with Alex Bettler

Other designers who have developed similar food performances include London-based Martino Gamper, whose Total Trattoria events involve him creating a temporary restaurant space and preparing a meal in front of invited guests, and Italian design group Arabeschi di Latte, who regularly present food-related happenings with invited chefs.

Dutch organisation Eat Drink Design (above) combines many of the trends mentioned above, curating dining spaces based around a long, communal table and decorated with the work of young designers; it then invites chefs to prepare meals in full view of diners, with dishes cooked and presented with theatrical flourish.

Epilogue: the future of food

Where will this love affair between food and design take us next? A number of scenarios suggest themselves.

The organic – and hence intrinsically sustainable – nature of foodstuffs means that they may increasingly become adopted by designers and industry as viable materials for products. Designers’ investigations into using food as a material, as outlined in this report, could perhaps be the start of a broader shift away from exploiting non-renewable commodities. The rise of bio-fuels as substitutes for fossil fuels and the emergence of starch-based plastics are two recent phenomenon that suggest how nature could be harnessed to grow raw materials, instead of depleting the earth’s finite mineral resources. This could bring the roles of chefs, designers and material scientists even closer together.

Meanwhile, designers seem increasingly less concerned with creating objects, and more fascinated with the way people interact with each other, the way they relate to objects and spaces, and how they can make these experiences more rewarding and meaningful. Since the preparation and consumption of food are the most fundamental of all human activities, it seems logical to conclude that designers will continue to explore how they can reinvent these experiences. This in turn could lead to novel new restaurant concepts and food typologies.

The kitchen’s increasingly central role in the home could perhaps develop further still to the point that there is no longer a single space in the home dedicated to food, but rather food could become integrated into every part of the home. It could be argued that the historical reasons why all the food storing and preparing devices are located in a single room are no longer valid.

Finally, high technology has struggled to make headway in the domestic kitchen; the recent emergence of induction hobs is perhaps the only major technical innovation to hit the kitchen since the microwave oven. But recent developments involving rapid prototyping, high-tech home farming, sophisticated low-energy systems and so on suggest that a technology-driven revolution of food making may be on the horizon.

Above: rapid-prototyped food as visualized by Philips Design’s Food Probe project

所有评论